Andersonstown News

A tale of two cities but the voice of one people Paper gave oppressed a voice when they most needed it. This was a paper of the people, by the people and for the people. The Andersonstown News came into existence on the 22nd of November 1972 as the successor to “Internment 71”, a news sheet published irregularly up to that point by the Andersonstown Civil Resistance Committee. “Internment ‘71” expressed the outrage of the local community at the introduction of internment without trial, which had affected numerous families from the greater Andersonstown area.

A tale of two cities but the voice of one people

Paper gave oppressed a voice when they most needed it.

This was a paper of the people, by the people and for the people. The Andersonstown News came into existence on the 22nd of November 1972 as the successor to “Internment 71”, a news sheet published irregularly up to that point by the Andersonstown Civil Resistance Committee. “Internment ‘71” expressed the outrage of the local community at the introduction of internment without trial, which had affected numerous families from the greater Andersonstown area.

Alongside the wave of grassroots resistance to internment in nationalist communities emerged new forms of independent community expression that challenged the traditional communications monopoly of the Catholic church and the middle classes.

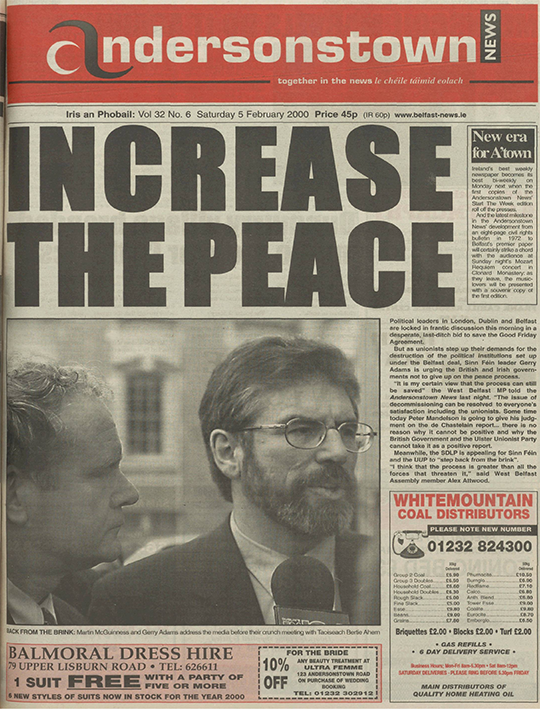

Andersonstown was no different, with “Internment ‘71” and local republican newsletters such as the Tattler or Volunteer, often published in haphazard fashion by amateur volunteers, acting as the forerunner to the Andersonstown News in voicing the concerns and opinions of the working class. The front page of the first edition of the ATN, physically printed in stacked, vertical, black-and-white columns, serves as a striking contrast to today’s modern, digitally, printed, colour tabloid format.

The absence of ads is remarkable. Moreover, the stories on it reflect the troubled times in which it emerged: 1972 was the worst single year of violence in the conflict which came to be

known internationally as ‘the Troubles’, as almost 500 people lost their lives across the North, the majority of those civilians, including the14 murdered by the paratrooper regiment in Derry’s Bloody Sunday. The fall of Stormont in March 1972 left a power vacuum which came to be filled by the British army, that utilised main force to subjugate nationalist communities through the removal of the ‘No Go’ areas in Operation Motorman in July 1972. Thus, it’s unsurprising that all nine stories on the front page related to the conflict sweeping West Belfast at the time in one way or another. British army arrests, harassment, and searches; shots fired at military posts in Casement and Trench House; bonfires lit in Andersonstown; and OAPs collecting funds door-to-door for internees are all splashed upon the front page.

Also remarkable is the cheeky sense of humour that marked the paper’s early reportage, reflecting the ‘Smart Alec’ wit of its early editorial room.

Source: 50th Anniversary edition.

Author : Tiarnán Ó Muilleoir